Aquatic Gardens: Galician Macroalgae or the Food Transformation

A story by Bénédicte Kurzen

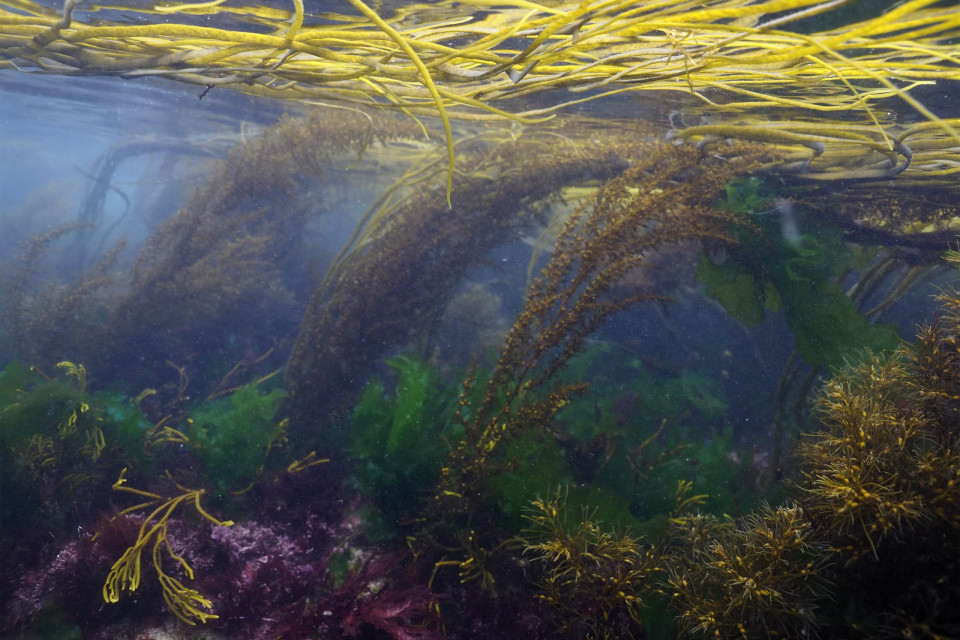

Think of the ocean as a garden. The Galician and Cantabrian seabeds are some of the richest in the world. The unique mix of waters gave birth to a magnificent landscape, home to hundreds of edible varieties of seaweed in all shapes and colours.

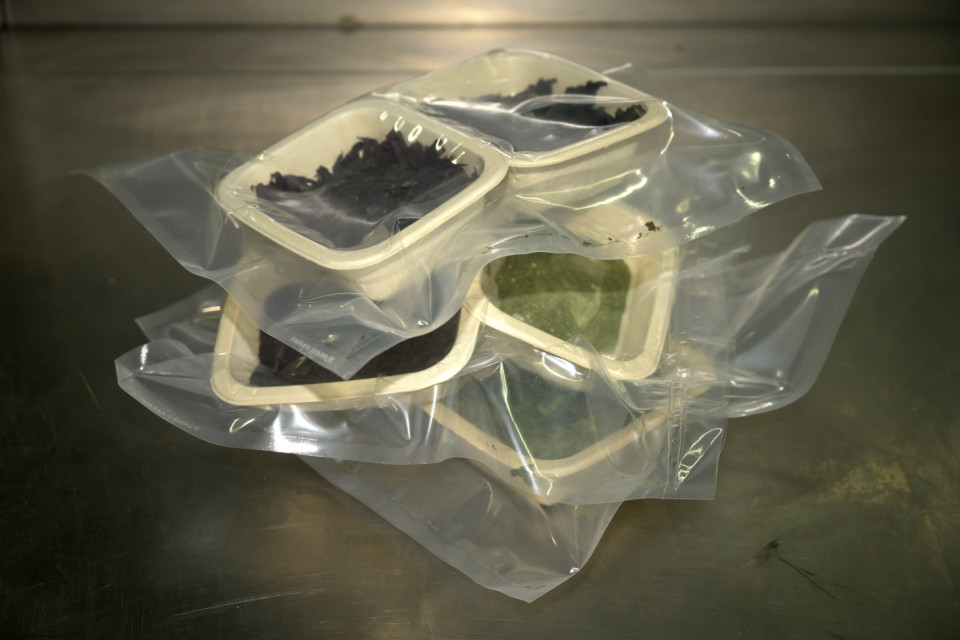

Antón Muiños is familiar with a great many. Having started diving at just five years of age, his passion grew into a company, Porto-Muiños, which now harvests seaweed and turns it into pasta, paste, or dried flakes for chefs all around the world.

Interest in algae has boomed in recent years. The European Commission declared it an important source of alternative protein for global food security. Algae is a perfect candidate for the Farm to Fork Strategy, one of the key components of the European Green Deal. But at the core of seaweed harvesting lies a key question: how can mass human consumption be reconciled with sustainability, accessibility, and cost?

These words feature in every one of Antón’s sentences. Concern etched on his face, he shows me a photo on his phone: an aquatic landscape that has been overharvested. The bare rocks evoke a cemetery, the dead spines like ghosts of the once-lush aquatic garden. While it has taken Porto-Muiños a decade to sell 100,000kgs of seaweed, new players see an opportunity for profit. In just one year, some of them harvested a massive 25,000kgs, says Antón.

Seaweed has many biological functions: fish lay their eggs, seashells and bottom feeders find refuge from predators. It is both a nursery and a hideout for many marine animals, promoting underwater biodiversity. It is also crucial to ocean health, helping regulate carbon dioxide, phosphorus, and nitrogen in marine ecosystems. But it is a sensitive creature. If one layer of this forest dies, the underlayer, which should be less exposed to light, dies too.

Antón is not alone on his mission to educate and promote respect for the sea. His son Tonio is teaching other divers to collect seaweed and seashells on a seasonal basis, to pick them with care to guarantee regrowth. Unexpectedly, the sun rears its head in this usually grey area of Spain. As it hits the water, all the underwater vegetation turns into a kitsch, saturated postcard.

In the Centro de Investigacións Científicas Avanzadas, Universidad da Coruña, Dr. Javier Cremades Ugarde walks from the fridge to the bubbling water tanks. On green strings, we can observe seaweed developing small branches.

This aquaculture system is protected from so many of the challenges wild algae is facing: global warming, poor water quality, invasive species, and so much more. If Europeans get used to the oceanic taste, this kind of farming is the only way to keep up with the demand for seaweed, says Antón Muiños. Dr. Cremades Ugarde’s nursery in his laboratory is just a few kilometres from the coast.